by Alexandria Searls

I live next to Meade Creek where the stream flows into a culvert underneath Chesapeake Street. It seems as if I hear the water when the windows are open, though the sound is faint on the average day, too faint to register with any definition, but comforting nonetheless. Before the City improved the drainage, I used to enjoy watching the creek rise in a storm. It would churn and escape its banks and threaten to reach the house, though it never did. At most it would come under the fence and then recede.

Meade Creek is vulnerable to the nearby storm drains, including one just beyond my front yard. One afternoon, my neighbor and I watched a painter pour a bleach mix down the drain, an action too quick for either of us to stop. There were dead fish in the stream the next day, and we didn’t see living fish for weeks.

In a drought, when there had been water restrictions, I witnessed two men in a commercial vehicle drive up and fill a plastic tank with the creek water. They used a pump and hoses; the tank, which was massive, took up half of the vehicle’s flatbed. There had been little enough water as it was–the minnows had been holding on in a few inches—so I hurried out of the house and confronted them. I wasn’t sure if any environmental law stood behind me. It seemed likely that people were able to syphon off as much stream water as they wished. The men pushed back with a few remarks, but then they took up their hoses and left.

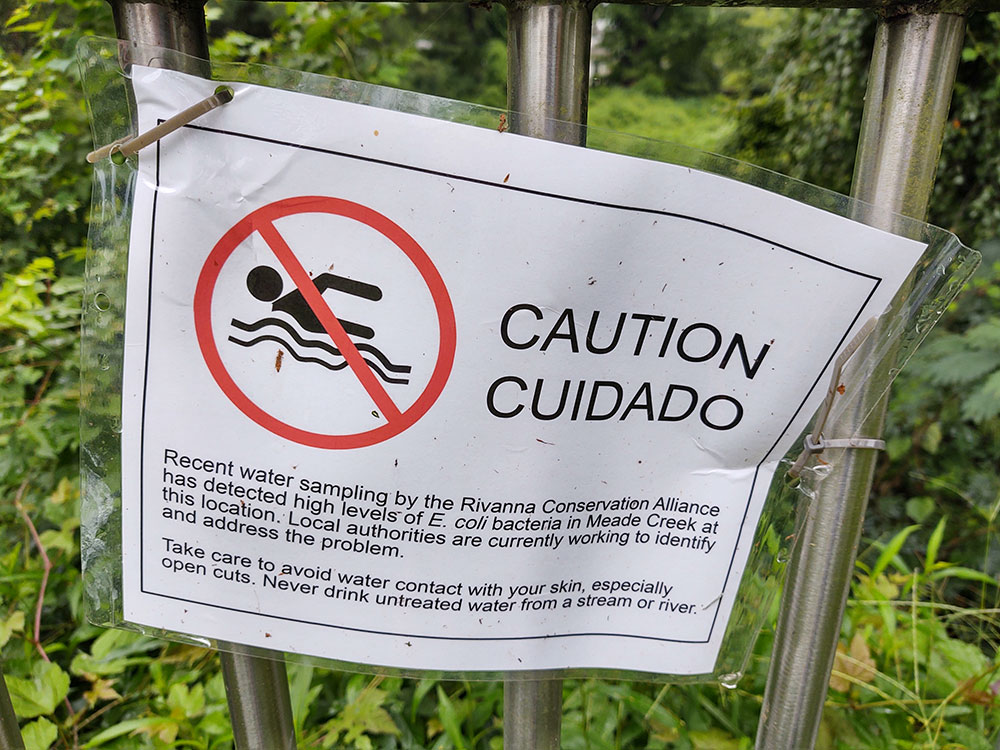

Between my house and the stream is a grassy pedestrian walkway owned by the City of Charlottesville. People walk their dogs and push their strollers along the right-of-way. Some parents with older children sit or stand as the children play in the stream. The stream itself resurfaces in Meade Park and continues to another culvert. That culvert is located underneath a pedestrian bridge, and this year, in August, I discovered a sign on the bridge, a warning laminated in plastic. The warning, made by the Rivanna Conservation Alliance, said that the stream was contaminated with high levels of E. coli. There should no wading, no swimming. You should avoid contacting the water with open cuts.

I was surprised. My emotional brain kicked in, not my scientific brain. How could contamination be so close? I had been living there for years; I hadn’t noticed a change. I called RCA, and they were wonderfully responsive. Claire Sanderson, the Monitoring Program Manager, came to my house and then led me to the points where the testing had happened. Her energy and lively Australian accent conveyed focus and problem-solving, and I learned the history of the E. coli monitoring. She explained the scale of E. coli testing, how under 410 MPN (the number of coliform organisms) per 100 mL was considered acceptable by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. Meade Creek at my location was over 3000 MPN.

I was surprised. My emotional brain kicked in, not my scientific brain. How could contamination be so close? I had been living there for years; I hadn’t noticed a change. I called RCA, and they were wonderfully responsive. Claire Sanderson, the Monitoring Program Manager, came to my house and then led me to the points where the testing had happened. Her energy and lively Australian accent conveyed focus and problem-solving, and I learned the history of the E. coli monitoring. She explained the scale of E. coli testing, how under 410 MPN (the number of coliform organisms) per 100 mL was considered acceptable by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. Meade Creek at my location was over 3000 MPN.

I am an underwater filmmaker and photographer and I had recently filmed the section of Meade Creek in the park, and with cuts on my hands from blackberry vines and gardening. I also had a beloved pet who strolled by the stream. I was concerned for my pet and for everyone else’s, while also knowing that animal waste could be part of the problem. The source of the high level of E. coli had not yet been identified.

Later that week, I went back to the bend in Meade Creek with my cameras. Birds were diving into the water there for a bath. They flew away as I sat down on mud and grass. The water was clear; the fish darting in deeper channels. I could not see contamination.

My scientific brain knew I couldn’t see the E. coli in the water, but now that the bacteria was so close to me, my emotional brain looked for shadows near the surface, or for some sign of decay or pathology. At home, I pored over the underwater footage, amazed at the clear water.

I met with Claire Sanderson again, this time at Trevillian’s Creek at the Lewis and Clark Exploratory Center, where I teach underwater filmmaking and photography. We walked in and along the stream; she found a frog and macroinvertebrates. I asked her if she would test the water, in particular where I bring children to wade and to use our cameras. The answer was a generous “yes.”

The result was back quickly. 23. Excellent. I could let out my breath.

In November, I told the story of the two streams to visiting field trips. “This is one of the reasons that science is so important,” I told them. “Science can detect things that we can’t see.”

At Meade Park, there are other things that I haven’t seen besides E. coli—frogs, and macroinvertebrates. Finding out about the E. coli levels drove home a fact that I had known, but not deeply enough, not until a threat was close to my house. When certain animals are missing, when they are invisible in effect, then there is a strong possibility that the water is impaired, perhaps by a toxin as unseen as the animals, but unlike them, very much present. It is my understanding that frogs are not sensitive to E. coli, but waste can be accompanied by chemicals, including pharmaceuticals. The general state of the water can often be read better from what is missing than from what is there.

Meanwhile, our emotional selves need time to adjust to the science. Even when we know, we may not know, if the issue hasn’t come close enough.