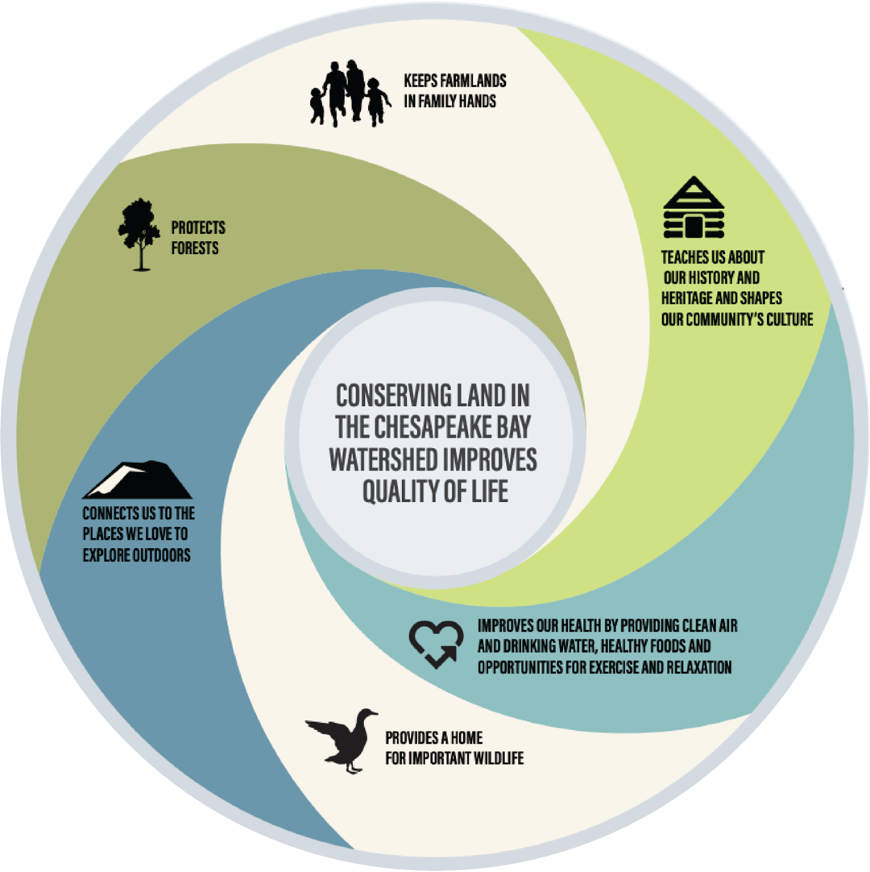

Best Management Practice (BMP) – refers to techniques found to be most effective and practical for a particular situation. In the case of stormwater, BMPs intend to reduce the volume of runoff and/or eliminate pollution and contaminants collected by runoff before reaching local waterways.

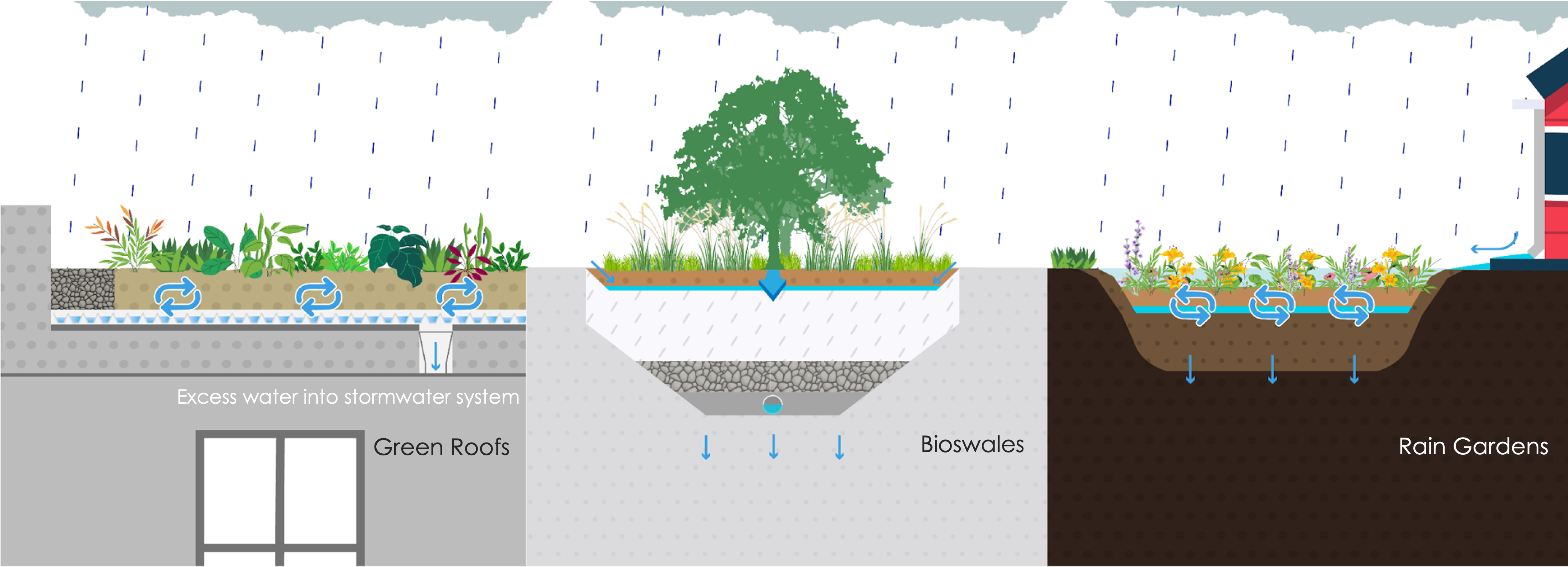

Environmental Justice – is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Green Infrastructure – natural or engineered systems that mimic the way nature works.

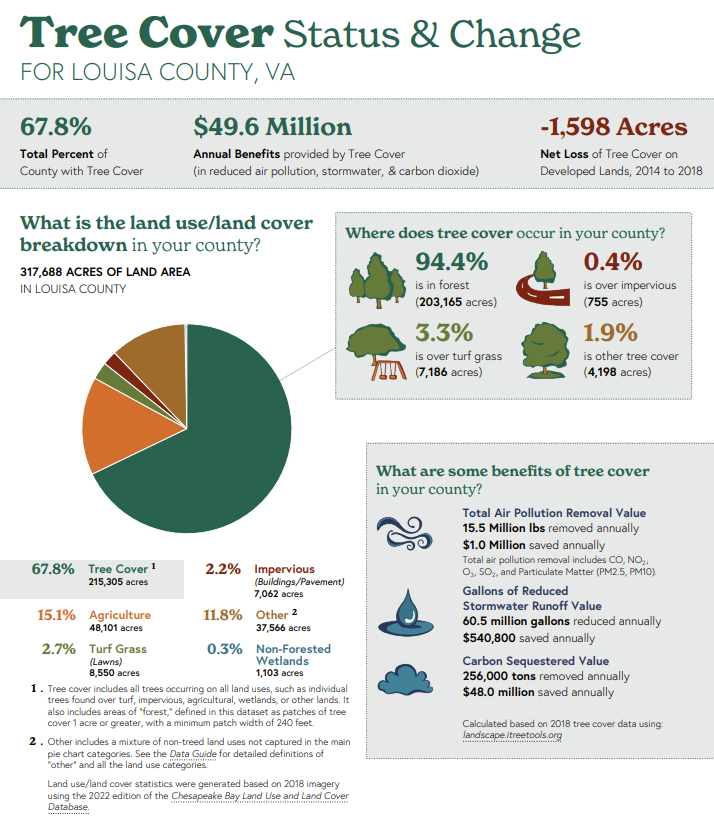

Impervious or Impermeable Surface – a surface that prevents water infiltration into the soil. They are typically made of man-made materials, such as asphalt, concrete, and metal.

Permeable (or pervious) – allowing water to pass through.

Stormwater Runoff– rain or snowmelt that runs off from impervious surfaces, such as rooftops, roads, and parking lots, into streams and ultimately the Bay itself, carrying pollutants, including nutrients, sediment, bacteria, and chemicals.

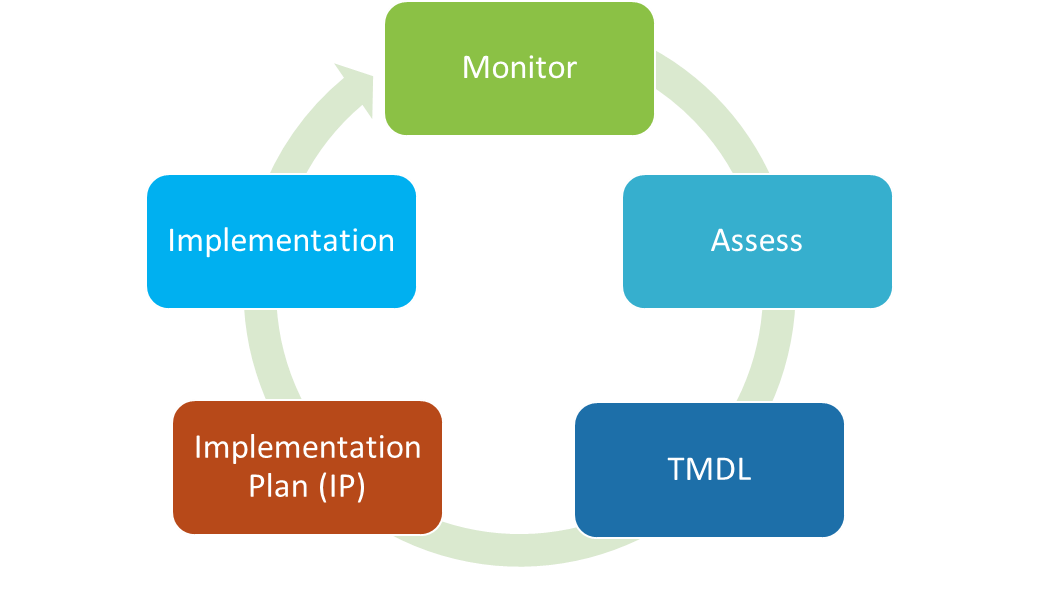

Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) – is a scientific determination of the maximum amount of a pollutant that a body of water can receive and still meet water quality standards.

Urban Heat Island Effect – a phenomenon that developed areas are warmer than their rural surroundings due to reduced natural landscape and heat generating human activities

Watershed Implementation Plan – a detailed, practical strategy for how Chesapeake Bay states and the District of Columbia, in partnership with federal and local governments, will attain the Chesapeake Bay TMDL.